[This post is primarily focused on a sometimes underappreciated, though by no means unrecognized, pre- Great Depression direct influence on the architects of The Chicago Plan, with brief mention of related influence on Minsky & Milton Friedman. There is a tiny nod to MMT as well]

It seems to often be assumed that The Chicago Plan developed in direct reaction to the Great Depression (perhaps in part because Irving Fisher’s slightly later bank reform proposals are indeed thought to be). For example, Phillips 1992 outlines the early stages of the Great Depression and writes “It is within this historical context that economists at the University of Chicago presented their proposal for reform of the banking system.” (1992, 6).

Economists and historians are of course well aware of the long history of bank reform proposals before this period. But two strands that are sometimes neglected are worth remembering, especially as they relate directly to current renewed interest in The Chicago Plan and indirectly to the work of Minsky which is also appropriately receiving increased attention (they also relate through the same line to Milton Friedman and aspects of his work that tie in closely to bank reform and Minsky).

The direct link is from radiochemist Frederick Soddy (in the social sciences, best known for his 1926 Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt) who has often been criticized as a “crank” writing outside of his field and dismissed – perhaps incorrectly, as we will see – as un-influential (Soddy is usually associated with Full Reserve Banking – he was against the gold standard and for floating exchange rates – and/or known for arguments related to ecological economics). The degree, directness, and timing of Soddy’s impact may have been underestimated.

[To be clear: this is not an attempt to revive Soddy’s views, ahead of but still a product of his times, especially the ones on the tangent of energy, although these have some relevance to economics and environmental concerns , but merely to point out a somewhat surprisingly direct influence from his work].

Phillips (1992) does not mention Soddy at all. Another prominent and detailed work on The Chicago Plan, Allen (1993), writes that:

“In March 1933, a group of economists at the University of Chicago, evidently with little if any influence from Soddy, gave very limited circulation to a six-page statement..”(Allen 1993, 705).

Yet it seems both Phillips and Allen overlook a key piece of evidence that shows that the hugely influential Frank Knight, one of the original architects of the confidential 1933 memorandum on banking reform (and teacher of Milton Friedman, George Stigler, James M. Buchanan and senior collaborator with the young Hyman Minsky) was directly influenced by Soddy’s work. Perhaps more remarkably, Knight was influenced well before the Great Depression.

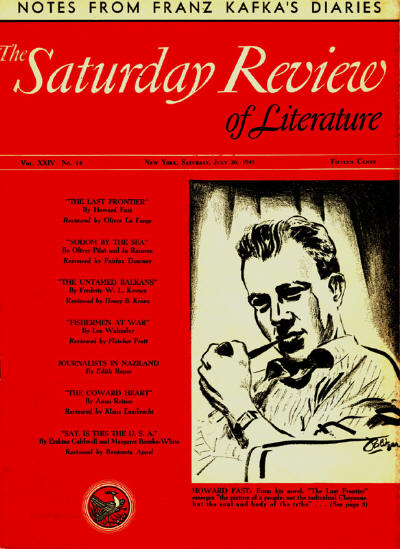

In 1927 Knight penned a short but in retrospect historically important review of Frederick Soddy’s 1926 Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt in The Saturday Review of Literature. Knight is highly critical of parts of the book, especially the mistakes Soddy as a non-economist makes and his neglect in realizing the extent to which economists had long struggled with banking and monetary issues. However, Knight also writes “These problems cannot be gone into here, but we can say with assurance that if this book leads economists to go into them as they deserve it will render the world a service of inestimable value.” Knight then concludes “The concepts of wealth, virtual wealth (money), and debt emphasize important and neglected distinctions, and in general it is a brilliantly written and brilliantly suggestive and stimulating book.” (Knight, 1927).

This is preceded by a still more remarkable passage, especially if we remember it was written in 1927 by a future primary author of The Chicago Plan and future teacher of Milton Friedman and especially developer of the Financial Instability Hypothesis, Hyman Minsky:

“The practical thesis of the book is distinctly unorthodox, but is in our opinion both highly significant and theoretically correct. In the abstract, it is absurd and monstrous for society to pay the commercial banking system “interest” for multiplying several fold the quantity of medium of exchange when (a) a public agency could do it at negligible cost, (b) there is no sense in having it done at all, since the effect is simply to raise the price level, and (c) important evils result, notably the frightful instability of the whole economic system and its periodical collapse in crises, which are in large measure bound up with the variability and uncertainty of the credit structure if not directly the effect of it.” (Knight 1927, 732).

PS The Peel Act, Soddy, Simons, Knight and Minsky

Henry Simons was of course a close colleague of Frank Knight (the second draft of The Chicago Plan was written by Henry Simons in close collaboration with Knight and other Chicago economists; they also edited an economics journal together I believe) and an even greater influence on Minsky than Knight (Wray writes that Minsky’s “biggest influences were…Henry Simons, but he also worked with Oscar Lange, Paul Douglas, and Frank Knight”; .Simons is thought to have been especially influential on Minsky through his 1936 article “Rules versus Authorities in Monetary Policy”, Moe 2012).

Simons seems to have been considering banking reform well before the Great Depression. He writes in a letter to Irving Fisher in 1933 that he had been interested from apparently as early as1923 in “trying to figure out the possibilities of applying the principle of the English Act of 1844 to the deposits as well as to the notes of private banks.” (Letter from Simons to Fisher, March 24, 1933, in Allen 1993, 706).

Much less known and rarely mentioned, Soddy had two earlier publications (and gave lectures) that discuss aspects of economics, his 1920 Aberdeen Lectures and 1921 Cartesian Economics: The Bearing of Physical Science upon State Stewardship.

Given that Soddy won a (real) Nobel Prize in 1921 I thought his other writings or economic lectures might have been noticed, and thought I would check if they seemed to have been of any influence on Simons, who, as we saw, said that he was interested in bank reform as early as 1923. However, as far as I can tell, neither of these works mentions the Peel Act nor much else that would probably have interested Simons in 1923. (Soddy cites as influences Silvio Gesell, who seems to have influenced Keynes as well, and Arthur Kitson – this is if nothing else a visually fascinating look at Kitson by the way)

At any rate, in the pre-Great Depression intellectual milieu surrounding Frank Knight and Henry Simons there seems to have been significant attention to ideas related to credit creation and financial stability, as expressed in Simons’ interest, apparently as early as 1923, in the Peel Bank Charter Act of 1844 and in Frederick Soddy’s documented influence on Knight in 1927, where he writes about bank credit-money creation leading to “frightful instability of the whole economic system and its periodical collapse in crises, which are in large measure bound up with the variability and uncertainty of the credit structure if not directly the effect of it.”

It is fascinating to see threads of connection running from modern work such Minsky, Steve Keen, or Benes & Kumhoff to the Bank Charter Act of 1844 (via Simons) and Frederick Soddy (via Knight), especially as Soddy was often dismissed as a crank writing outside of his field.

The MMT Bit:

I ran across these in Soddy 1921:

“Wealth is a flow, not a store…I can conceive no nation so barbaric as to regard gold as a store of value. Demonetise it and where is its value? Not a gold mine would be at work on the morrow.” (Soddy 1921)

money “ought to bear precisely the same relation to the revenue of wealth as a food ticket bears to the food supply or a theatre ticket to a theatrical performance.” (Soddy 1921)

A hint of MMT here – stocks & flows, state theory of money, and money as a token or a ticket. All within a few paragraphs.

Works Cited:

Allen William R. 1993, “Irving Fisher and the 100 Percent Reserve Proposal”, Journal of Law and Economics, 36: 2, 703-717.

Knight, F. (1927), “Review of Frederick Soddy’s ’Wealth, Virtual Wealth, and Debt’”, The Saturday Review of Literature Vol. 3 no. 38 (April 16), p. 732. Full text here

Knight, F. (1933), “Memorandum on Banking Reform”, March, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, President’s Personal File 431.

Moe, Thorvald Grung 2012 Control of Finance as a Prerequisite for Successful Monetary Policy: A Reinterpretation of Henry Simons’s “Rules versus Authorities in Monetary Policy” Levy Economics Institute,Working Paper No. 713

Phillips Ronnie J., 1992, “The ‘ChicagoPlan’ and New Deal Banking Reform” Levy Economics Institute, Working Paper No. 76

Soddy,Frederick, 1920, Science and Life -AberdeenAddresses [1915-1919] (hard to find – ISBN = 0548629781 and 978-0548629789)

Soddy,Frederick, 1921, Cartesian Economics: The Bearing of Physical Science upon State Stewardship.

Soddy,Frederick, 1926, Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt. The solution of the economic paradox. George Allen & Unwin.

Wray, 2012, Why Minsky Matters (Part One) March 27, 2012 http://www.multiplier-effect.org/?p=4172

Note: This is by no mean an attempt at a resurrection of Soddy’s work, although Soddy 1926 certainly has some important points in it and in retrospect is clearly more than just the work of a “crank”. The main point here is simply to show that there is documented evidence that Soddy influenced Knight well before the great depression. Given Simons’ direct influence on both Friedman and Minsky, it is also interesting the evidence that Simons was, like Knight, interested in credit-money reform well before the Great Depression. Soddy should also be recognized for his influence on concerns about economic growth and the environment, remarkable for his time [although perhaps not surprising for someone educated in physics and chemistry].

April 1 2019 Update: The new book is finished and available! Live on Amazon here –

1000 Castaways: Fundamentals of Economics

More of Soddy’s economic writings:

Books

Soddy, Frederick, 1931, Money versus Man. London: Elkin Mathews & Marrot

___________ 1934, The Role of Money,London: George Routledge & Sons.

Other

“Economic ‘Science’ from the Standpoint of Science”, The Guildsman, No. 43, July 1920.

‘Money’, A lecture delivered to the Oxford City Labour Party in Ruskin College, 21st January 1923.

“What I think of Socialism”, Socialist Review, August 1928, pp. 28-30.

“Unemployment and Hope,” Nature, 1930.

Poverty Old and New, lecture to the New Europe Group,London, published by The Search Publishing Co. Ltd., 1932

“A Physical Theory of Money”, paper to the Liverpool Engineering Society, Transactions of the Liverpool Engineering Society, 56, 1934

“The Role of Money”, The Oxford Magazine, June 7. 1934

“TheNew BritainMovement”, Supplement to New Britain, June 20, 1934

‘Money as Nothing for Something’, Garvin’s Gazette, March 1935.

(A later volume – Garvin’s Gazette)

‘The Gold Standard Snare’, Garvin’s Gazette, July 1935.

The “Pound for Pound” System of Scientific National Monetary Reform in Montgomery Butchart (editor) To-morrow’s Money, Stanley Nott. 1936

‘Money and the Constitution: report of the Prosperity Campaign Conference’, DigswellPark, August 1936

Credit, Usury, Capital, Christianity, and Chameleons, The Economic Reform Club. 1937

The Budget, synopsis in one hundred verses of the author’s ‘Reformed Scientific National Monetary System’, Knapp, Enstone, Oxon. 1938

Money and the Constitution, Knapp, Enstone, Oxon. 1938

Social Relations of Science, Nature, 141, 784-5., 1938

Abolish Private Money, or Drown in Debt: Two Amended Addresses to our Bosses by Walter Crick and Frederick Soddy, 1939

“Finance and War”, Address to members of the Parliamentary Labour Party at the House of Commons , Nature, 147, 449, 1940

‘The Arch-Enemy of Economic Freedom: what banking is, what first it was, and again should be’, A reply to the Rt. Hon. R. McKenna’s ‘What is Banking ?’, Knapp, Enstone, Oxon, 1943.

Demand For Monetary Reform inEngland, a letter sent to the Archbishop of Canterburyand nine other clerical authorities, signed by thirty-two monetary reformers, Authored by Soddy and Norman A. Thompson 1943

‘Present Outlook: A Warning-debasement of the currency, deflation, and unemployment’, For Local Administration Authorities, September 1944.

(the more obscure works are from http://booksinternationale.info/pipermail/freshink/2009-July/002319.html )

Off topic but – While looking for Saturday Review of Literature Covers I ran across a number of interesting ones-

Saturday Review of Literature August 8, 1942 Sergei Eisenstein Cover